Better Use of Data Will Optimize the Benefits

By Beia Spiller, Environmental Defense Fund

Thanks to improvements in technology, it’s easier than ever to be green.

Solar panels and electric vehicles (EVs) are two prime examples of technologies that can help people minimize their environmental footprint without sacrificing comfort or having to radically change their daily behavior. But the question still remains: How much of an environmental benefit do these technologies actually produce? And are there actions that owners of these technologies can take to minimize their pollution footprint even more?

My colleagues and I recently published a paper in Energy Economics, attempting to answer these two questions for households in Austin, Texas. Our study took place in the Mueller residential neighborhood and focused on a group of homes that are part of Pecan Street Inc., a living smart-grid laboratory with the largest customer energy-use database on the planet. Using detailed household-level data from 2013 to 2015, we were able to track solar panel performance and EV use and charging patterns and match these actions to two important environmental impacts: water use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Our paper confirms that, in Texas, using residential solar panels instead of central-grid power leads to decreased water consumption and air pollution, and driving an EV instead of a gasoline vehicle generally reduces the household’s water and emission footprint, even though EVs charge from the grid. Moreover, our analysis demonstrates how carefully examining energy-use data can help us make sure we’re maximizing clean energy’s benefits.

Courtesy: Environmental Defense Fund

The Energy-Water Connection

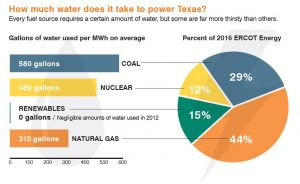

Most people know that burning fossil fuels—whether to create electricity or drive gasoline vehicles—emits gases that pollute the air. But how do the central electric grid and cars use water?

Water is used to produce many forms of energy, including both fossil fuel-based electricity and gasoline. A natural gas or coal plant requires large quantities of water both for processing materials and cooling the power plant. The production and refinement of gasoline also uses a lot of water; in fact, it takes about four gallons of water to produce one gallon of gasoline.

Wind and solar PV, on the other hand, need virtually no water to create power, and they do not emit GHGs or other pollutants in the process.

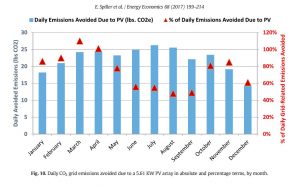

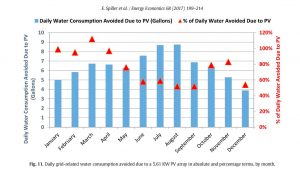

The Solar Findings

Because solar panels consume no water and emit no pollution, installing a solar panel allows a household to dramatically reduce both the water use and air pollution associated with grid electricity.

In fact, we find that solar panels in Texas can reduce a household’s combined footprint by about 75 percent.

In fact, we find that solar panels in Texas can reduce a household’s combined footprint by about 75 percent.

In Texas, the main power sources are natural gas and coal—even when the sun is shining. So, if you’re getting some or all of your power from your own solar panels, you’re avoiding using the grid’s thirsty, high-GHG-emitting electricity.

Want to shrink your environmental footprint even further? By facing solar panels south, households can capture more sun throughout the day. This may conflict with local electric systems’ attempts to maximize production during periods of peak demand (generally in the afternoon when people are getting home from school and work). For example, Pecan Street provided subsidies for solar owners in their community who face their panels west to maximize generation during that afternoon peak period. However, those west-facing panels produce less energy over the course of a full day than the south-facing panels, which means the household requires more water use and emissions from the central grid.

Want to shrink your environmental footprint even further? By facing solar panels south, households can capture more sun throughout the day. This may conflict with local electric systems’ attempts to maximize production during periods of peak demand (generally in the afternoon when people are getting home from school and work). For example, Pecan Street provided subsidies for solar owners in their community who face their panels west to maximize generation during that afternoon peak period. However, those west-facing panels produce less energy over the course of a full day than the south-facing panels, which means the household requires more water use and emissions from the central grid.

This contradiction highlights the importance of data analysis. A better understanding of hourly versus overall energy usage and emissions can inform electric system policies and pricing that lead to a reduction in total costs—including costs to our environment.

The EV Findings

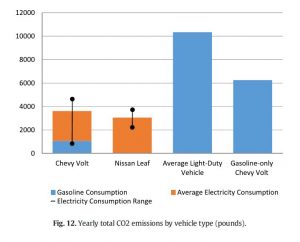

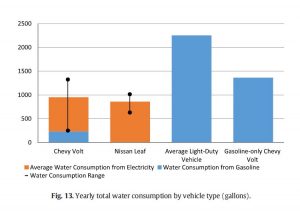

Understanding electric vehicles’ environmental impact by these measurements is a bit trickier, because EVs avoid gasoline, but they also charge using the grid, which in Texas is largely powered by fossil fuels. Our paper, therefore, tested whether EVs in Texas really do protect the environment—in this case by reducing water use and GHGs.

To quantify the environmental benefits of EVs, we needed to think about the kind of vehicle the household would have driven had it not purchased an EV. Vehicle owners have many choices in the marketplace, and fuel efficiency is not the only deciding factor. For example, a family with many children or someone who needs to haul a trailer may not be willing to sacrifice vehicle size or horsepower in favor of a more compact and efficient vehicle. On the other hand, a person who likes small cars may place greater weight on fuel efficiency; this person’s alternative to an EV is more likely to be a hybrid, whereas the large family’s alternative vehicle is more likely to be a minivan.

To quantify the environmental benefits of EVs, we needed to think about the kind of vehicle the household would have driven had it not purchased an EV. Vehicle owners have many choices in the marketplace, and fuel efficiency is not the only deciding factor. For example, a family with many children or someone who needs to haul a trailer may not be willing to sacrifice vehicle size or horsepower in favor of a more compact and efficient vehicle. On the other hand, a person who likes small cars may place greater weight on fuel efficiency; this person’s alternative to an EV is more likely to be a hybrid, whereas the large family’s alternative vehicle is more likely to be a minivan.

Understanding what the alternative choice would have been is key in measuring the environmental impact of an EV: the less fuel-efficient the alternative vehicle, the better the EV is for the environment. For example, if you switch from driving a gas-guzzler to an EV, that’s more beneficial than switching from a hybrid. In fact, we find that if the household’s alternative-choice vehicle is a hybrid, using an EV can actually increase its net water use—the reduction in gasoline use is very small due to the high efficiency of the hybrid, and the EV is charged with thirsty grid electricity.

That said, though the benefits still vary with the efficiency of the alternative vehicle, we find that EVs always reduce overall GHG emissions.

Our findings related to EVs suggest three distinct policy solutions:

- Ensure that vehicles such as SUVs and trucks have electric offerings, which manufacturers like Tesla and Volvo are already working on. This will help steer those who require larger-sized vehicles toward choosing an electric option, thereby drastically reducing their environmental footprint.

- When people purchase a new EV, a well-designed rebate program that pays them to surrender their inefficient vehicle (such as an improved version of the 2009 “Cash-for-Clunkers” program) could lead to even greater reductions in the environmental impacts of driving.

- Ensure that more grid electricity comes from solar and wind, thereby further improving the water- and emission-intensity of EVs. Especially as EV adoption increases, having a clean grid will help us achieve a more environmentally friendly transportation sector.

Conclusion

Solar panels and electric vehicles will help pave the way to a cleaner future, but we must dig into the details to ensure we maximize the environmental benefits. The more data available to examine, the better our decision makers can design energy programs and incentives to improve our environmental footprint.

[Acknowledgement: Figures 10, 11, 12, and 13 courtesy of Energy Economics.]

Dr. Elisheba Spiller is a Senior Economist at Environmental Defense Fund. She has expertise in domestic climate and energy policies, with a main focus on electricity pricing and regulation. She has a Master’s and PhD in Economics from Duke University