Proposed ERCOT grid rule change could affect some community solar projects

By Joshua Rhodes, The University of Texas at Austin

April, 2019

The stakeholders of the organization that runs most of the Texas electricity grid, the Electricity Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), are considering a market rule change labeled Nodal Protocol Revision Request 917 (NPRR 917) that could affect the economics of community solar systems. However, the proposed rule change, if enacted, would not affect residential solar systems or community solar systems under 1 MW of capacity.

In short, the rule change seeks to treat smaller generators, including some community solar projects, more like the large generators on the system.

A Bit of Background

Wholesale electricity markets are complex networks in which a relatively small number of large generators are constantly ramped up and down to meet our ever-changing demand for electricity. Every time you switch on a light or stream a show on Netflix, a power plant somewhere ramps up to meet the extra demand you create. As demand changes on the grid, so do electricity prices.

In fact, prices change about every five minutes, and they can vary across more than 13,000 locations around the Texas grid. Prices may differ depending on how electricity is being supplied to or extracted from the system, as well as to account for any congestion on power lines (think road traffic that limits the number of cars that can get from point A to B) that may exist at any place at any time.

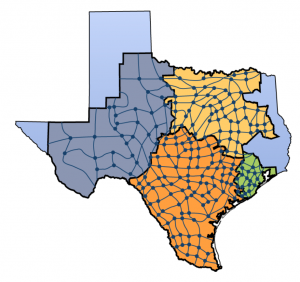

Figure 1: The ERCOT grid showing nodes as blue dots and load zones as different colored shapes. Each of the dots gets a new price every five minutes and the price of the zone is the load-weighted average price of the nodes within that zone. This figure is a simplified rendering, since there are more than 13,000 locations that are automatically updated with new prices every five minutes.

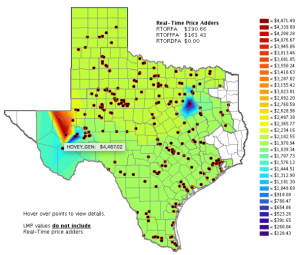

Sometimes, price differences between nodes along the grid can reach into the thousands of dollars per megawatt-hour, depending on the location of those nodes. Prices at some nodes can even go negative—power plants actually pay the grid to take their power away. Today, most negative prices usually occur when overall demand is very low (spring and fall nights when we are neither heating nor cooling our homes) and wind output is very high (also spring).

Although the dynamics of the wholesale market ultimately determine electricity prices for everyone in Texas, we may not feel the impact, up or down, until our next rate adjustment many months or years later. But this constant trading of energy for dollars directly impacts the profitability of individual power plants and the long-term future of the energy mix in ERCOT.

While there are thousands of nodes, they are contained in four major ERCOT zones: North, South, West, and Houston. The prices at these zones also change every five minutes, but these zonal prices are an average (load-weighted) of the many nodes within each zone.

When large generators such as natural gas, coal, wind, nuclear, and utility scale solar plants produce electricity, they receive compensation at the nodal price (one of the 13,000) located at its grid connection point. This pricing scheme is designed to incentivize generators to build in places where power is needed (high demand areas where nodal prices are high) and to discourage building in places where additional electricity is not needed (where nodal prices are low).

The wholesale market is called so because it is composed of buyers and sellers. The buyers are you and I using our air conditioners, via the utilities that act as our brokers. The sellers are the power plants. The grid operator (ERCOT) oversees the whole system to make certain that no single player gets too powerful so as to stifle competition.

So What Does All This Have to Do with Community Solar?

Currently, when community solar systems, or any generator between 1 and 10 MW, produce electricity for the grid, they are paid not on nodal prices like larger generators, but the averaged zonal price. As a result, the siting of community solar projects within a zone is not of critical importance, because even if the node closest to a community solar project is experiencing low prices, the community solar plant itself could be earning a higher zonal price. On the other side, unless all prices are uniform across the zone, there is always a node in the zone that is experiencing a higher price than what the solar project is earning.

Recently ERCOT has begun to focus on these smaller generators. In 2018, stakeholders passed the predecessor to NPRR 917, NPRR 866, which authorized ERCOT to map these resources to the appropriate node.

Figure 2: Figure showing price differentials between nodes in ERCOT reaching thousands of dollars per megawatt-hour during the 2018 summer peak.

NPRR 917 seeks to change the current arrangement and treat community solar systems more like larger generators and compensate them at nodal price levels. This means that community solar projects will be more directly exposed to the wholesale market, and if they are located at a node that often experiences lower prices, they might earn less revenue. If they are located near higher priced nodes, they might earn more revenue than they do today.

The current proposal for NPRR 917 will likely grandfather generators under 10 MW that were in operation as of January 1, 2019. These projects could make a one-time choice to opt out of nodal pricing for twenty years. Additional compromises among stakeholders will no doubt occur before NPRR 917 reaches the ERCOT Board of Directors for final approval. Implementation will most likely occur around June.

The overall effect of the rule will be to extend the market structure down to the level that could include some community solar projects. It would not only force community solar developers to be smarter about where they build, but also provide a stronger price signal as to where community solar projects could be most useful on the grid (at higher priced nodes).

In the end, the economics of community solar projects are dependent on the types of contracts that they negotiate with their off takers, the customers that choose to buy their power. There are many ways to structure these contracts, though that’s a topic for another article.

Since community solar projects are compact in size (two to four acres for 1 MW of capacity), they can be built in more places. If NPRR 917 is adopted, higher-price locations might become more apparent for community solar developers to exploit and the more attractive economics could lead to more community solar development.

Joshua D. Rhodes, PhD, is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in The Webber Energy Group and the Energy Institute at the University of Texas at Austin. His current research is in the area of smart grid and the bulk electricity system, including spatial system-level applications and impacts of energy efficiency, resource planning, distributed generation, and storage.

Editor’s Note: You may also enjoy another article by the author published a few days ago in the Waco Tribune-Herald, Texas Perspectives: State legislation unfairly targeting wind, solar initiatives.